HAVELI (Urdu: حویلی, Hindi: हवेली) is the term used for a private mansion in Pakistan and North India. The word haveli is of Persian origin, meaning "an enclosed place".

HAVELI (Urdu: حویلی, Hindi: हवेली) is the term used for a private mansion in Pakistan and North India. The word haveli is of Persian origin, meaning "an enclosed place".These haveli were 1st built by the wealthy and highly successful merchant class Indians who were largely from Rajasthan and Gujarat.

In my research, I have found out that there are essentially 3 distinctive styles of haveli as there were 3 groups of merchants who have incorporated differing and distinctive features in their houses.

First, there are the Bohra manzil (or Bohra buildings) of Siddhpur (Gujarat) that are laid out formally along broad avenues constructed and decorated almost in the European style.

Then we have the Shekhavati havelis which are justly famed for their frescoes.

Then we have the Shekhavati havelis which are justly famed for their frescoes. Lastly, we have the haveli of Ahmedabad (where Rajiv is from) which are renowned for their remarkable and almost extinct decorative wood carving.

Lastly, we have the haveli of Ahmedabad (where Rajiv is from) which are renowned for their remarkable and almost extinct decorative wood carving. Different as they may seem, there are 2 distinct areas that all 3 types of havelis share in common. Firstly, driven by a spirit of rivalry between themselves and an intense competition to inhabit the best and the biggest havelis, the owners often spared no expense and were consistently generous patrons of arts and crafts, who engendered a quality and diversity of creativity that will probably never be achieved again. Sadly, and that's the 2nd area of commonality, many of these havelis, be it Bohras' , Marwalis' or the erstwhile merchants' of Ahmedabad, are now left to deteriorate and decay as their owners have moved on.

Different as they may seem, there are 2 distinct areas that all 3 types of havelis share in common. Firstly, driven by a spirit of rivalry between themselves and an intense competition to inhabit the best and the biggest havelis, the owners often spared no expense and were consistently generous patrons of arts and crafts, who engendered a quality and diversity of creativity that will probably never be achieved again. Sadly, and that's the 2nd area of commonality, many of these havelis, be it Bohras' , Marwalis' or the erstwhile merchants' of Ahmedabad, are now left to deteriorate and decay as their owners have moved on.This is thus my feeble attempt to help in generating more interest in havelis (and thus encourage more preservation of these wonderful architecture) while researching on how I can convert "Termite House" to "Bombay Tea Leaves- Where the Party Never Ends".

Here are some of the research material that I found to be of interest. I am especially in love with the Patwon Ki Haveli which apparently took 50 years to complete.

BOHRAS IN GUJARAT

The following is an extract from the book Traditional architecture: House Form of Bohras in Gujarat by Madhavi Desai.

The following is an extract from the book Traditional architecture: House Form of Bohras in Gujarat by Madhavi Desai.They express the totality of a relationship between man and society. These settlements are characterized by consistency over a long period of time and a strong integration of the built environment with the patterns of life. The traditional habitats of the Islamic community of the Bohras (generally referred to Daudi Bohras) in Gujarat, found in cities and towns such as Surat, Siddhpur, Dahod, Godhra, Kapadvanj, Khambhat, Ahmedabad, Palanpur, Bhavnagar, Dholka, Surendranagar, Morbi and Jamnagar, etc. are excellent examples of traditional architecture rooted in the regional landscape.

(Pic Right: Typical window of a Bohra home) There are two broad categories of Bohrwads: one has an organic layout while the other is strictly geometrically laid out. The structure of a typical organic Bohrwad is inwardly oriented, where the houses are arranged in an introverted neighborhood form. Most Bohrwads have a formal entrance where gates used to be closed at night in the past. The houses in a Bohrwad are typically grouped around a street and these form a mohalla; several mohallas form a Bohrwad. Each mohalla is an exogamous unit and may have fifty to a hundred houses.A traditional Bohra house, seen in its cultural and spatial context, creates a sense of place in a distinct domestic setting. The house can almost be considered a metaphor for the social system. Male dominance is strong and women are commonly segregated from men not belonging to their immediate families. Gender is important as an organizing theme in dwelling layouts and use of spaces. For the Bohras, religion is a way of life that also provides a civic code, influencing social behavior and interactions. The Bohra house is usually always oriented according to the cardinal directions as per the practice in the region. The urban house has at its core a set of spaces, which in their sequence and proportions are identical to those of the rural dwelling. It is basically a deep house-plan with three (or four) sequential rooms one behind the other.

Facade of a storied house.

Facade of a storied house.

Facade of a house in Kapadvanj.

The regional model was not only adapted by the Bohra community but also taken to its maximum potential with necessary adjustments due to the religious tenets of Islam. Certain concepts like clear separation between the public and private, the necessity for an in-between zone at the entrance level, the male/female divide, seclusion of women, the intense need for privacy, etc. have brought about specific devices and spatial configurations that reflect the tenets of the religion. Generally a joint family system is followed. The kitchen is common to all and it becomes central to the family. The spatial hierarchy in the typical Bohra house has a sequence of otla (entrance platform), deli (arrival space), avas (courtyard), parsalli and the ordo (room). The upper floors mainly house the bedrooms and the agashi (terrace). The Bohrwad is made up of three to four storeyed-high houses arranged in a high-density layout. The individual courtyard becomes an air and a light shaft where the cooler air sinks below and the hotter air escapes out of the roof.

The Bohras have adopted the regional tradition of Gujarat of making facades with intricate details in wood. They accommodated a whole range of styles, building materials and decorative treatments resulting in attractive facades (and streets) that have become the hallmark of their vernacular architecture. In contrast to Islamic philosophy, there is exterior display and frontal exposure as the facades are rich in variety and aesthetic expression. They create a sense of enclosure and a play of light and shadows by using of solids and voids. Through the display of several textures and patterns, they express balance and harmony within a predominantly symmetrical composition. The surface of the facade is visually broken by ornamented columns, brackets and mouldings, at times bringing multicolored cohesion to the streets.

The facades enhance the totality of the physical ambience of the built environment. Built by craftsmen, they reveal their comprehensive understanding of the elements of design, the nature of the building materials and versatility of craftsmanship. The unity of facades has been achieved by similarity of building types, materials of construction and commonality of a design vocabulary. There is a lot of aesthetic attention paid to the making of the windows, entrance doors, columns, brackets, grills and other elements. In the embellishments they use only non-figural and abstract geometrical patterns as per the Islamic tradition, which rejects animate objects (gods, people, birds and animals) in carving.

The facades enhance the totality of the physical ambience of the built environment. Built by craftsmen, they reveal their comprehensive understanding of the elements of design, the nature of the building materials and versatility of craftsmanship. The unity of facades has been achieved by similarity of building types, materials of construction and commonality of a design vocabulary. There is a lot of aesthetic attention paid to the making of the windows, entrance doors, columns, brackets, grills and other elements. In the embellishments they use only non-figural and abstract geometrical patterns as per the Islamic tradition, which rejects animate objects (gods, people, birds and animals) in carving.

Pic left is a typical entrance to a house in Kapadvanj.

In every vernacular tradition, certain elements/objects get developed in the house that are expressive of the users’ cultural attitudes and also communicate symbolic meanings to the onlookers. A lot of variation was perceived in the types of zarookhas (floor projections) that were incorporated as a part of the design of facades in various Bohra housing in Gujarat. The Bohras developed this element to its full potential. The impact of cultural attitudes is seen in the full enclosure of the balcony in many of the Bohra houses. One hardly sees any person standing in the external zarookha or the balcony and interacting because the Bohra life-style emphasizes privacy, formality and internalization. The enclosed balcony takes the form of a luxurious window-seat referred to earlier in the case of the typical house in Siddhpur. The seat is approached from the deli and a space for it is created next to the entrance steps. This bay window has iron screens on the outside. Spacious and well-lit, the seat with mattresses and pillows is used for a group of women to relax and converse, or for a lone woman to pass her time looking out on the street while doing embroidery.

Since both the Hindu and Bohra house types are based on a common regional house form, there are more similarities than differences, where the differences generally occur through subtle interventions due to the required change in the cultural use of domestic space. It is noteworthy that in spite of the limitations of the shared-parallel-walls typology, a considerable degree of flexibility has been achieved in the spatial layout in response to sub-cultural or climatic variations.

A typical street in a Bohra neighborhood in Sidhpur.

The Bohra habitations represent a living tradition of Gujarat. However, some of the elaborately carved and richly decorated houses are deteriorating at a fast rate and are, at times, being sold to antique dealers who dismantle them completely for selling their decorative elements and teak wood. This situation is getting desperate and urgent steps are required for conservation of this valuable heritage. Conservation of individual monuments or precincts of an urban fabric poses a complex challenge. Unless the people of the community can be motivated to get directly involved and have an urgent desire, substantial and large-scale conservation efforts become impossible. The crucial fact to remember is that the Bohras are conservationists and promoters of art may be unconsciously. If they are further encouraged by a strategy for conserving entire Bohrwads, it will help continue the momentum of cultural preservation in order that some of the best historic examples of regional domestic architecture in Gujarat are not lost.

The book "Traditional architecture: House form of Bohras in Gujarat" can be bought at

National Institute of Advanced Studies in Architecture

CDSA Campus, S. No. 58 & 49/4, Bawdhan Khurd,

Pune Paud Road, PUNE 411 021

Tel: (20) 2295 2262, (20) 6573 1088

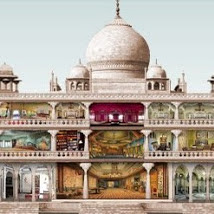

Located at the town center of Jaisalmer in Rajasthan, Patwon Ki Haveli was constructed by a Marwari business man Guman Chand Patwa and his five sons.

Located at the town center of Jaisalmer in Rajasthan, Patwon Ki Haveli was constructed by a Marwari business man Guman Chand Patwa and his five sons.Before the development of the sea trade Jaisalmer was in fact an important part of the silk route connecting India to Persia and the rest of the middle east. The Patwons were rich merchants dealing in gold, brocade and silver.

Built between 1800 to 1860, Patwon ki Haveli has five havelis located within the complex , one for each son. It was estimated that a total sum of Rs 10 million was spent on the construction of the complex. The project took place during the time when the people of Jaisalmer were facing famine and the revenue generated from its construction ensured the survival of many of the people. Hindu and Muslim craftsman hailing from Gujarat, Malwa and Sindh worked hand in hand in constructing these havelis.

After the construction of the Bombay shipyard, the trade route shifted to sea and the importance of Jaisalmer as a trade center started to decline. The business families of Patwa then migrated to Madras, Maharashtra and Bengal and the havelis were left largely uninhabited.

After the construction of the Bombay shipyard, the trade route shifted to sea and the importance of Jaisalmer as a trade center started to decline. The business families of Patwa then migrated to Madras, Maharashtra and Bengal and the havelis were left largely uninhabited.Sometime in 1965, while traveling by helicopter over Jaisalmer, the then Prime Minister of India, Mrs Indira Gandhi saw the splendour of this building and was so beguiled that she took immediate steps to conserve this building. Patwan Ki Haveli was bestowed with the status of Heritage Building by the Rajasthan Government and the management of this Haveli was given to the Raj Kumar Kothari family trust.

Mr Raj Kumar Kothari converted part of the Haveli into 12 galleries displaying some of the his own personal collections. These collections include a turban collection, locks collection, paintings and fans. The turban gallery displays different types of turbans used by people from different castes and cultures of the state. Another gallery displays differe

nt types of musical instruments used by different folk communities. There is also a gallery displaying different types of locks used in those days. These locks were for secret places like the basement or an alcove behind a painting where owners stored their treasure and other valuables and the location was passed to the next generation by oral communication. One such location on display was a "safe" behind a painting.

nt types of musical instruments used by different folk communities. There is also a gallery displaying different types of locks used in those days. These locks were for secret places like the basement or an alcove behind a painting where owners stored their treasure and other valuables and the location was passed to the next generation by oral communication. One such location on display was a "safe" behind a painting.The Haveli is a magnificient example of the Indo –Islamic architecture. Inside the havelies apart from galleries,there is also a temple, a drawing room, dining hall, bedrooms and kitchen.

The entry fee for Patwon Ki Haveli is Rs 30 for Indians, and Rs50 for foreigners. Charges for video camera is Rs 40 and still camera is Rs 20. A causal tour of the Haveli will take 30 to 45 minutes.